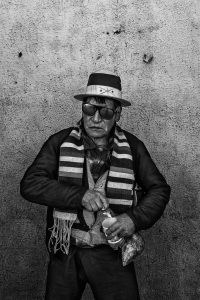

Potosí is a disconcerting example of how the economic system that enriches the industrialised world is facilitated by people who will never benefit from it themselves; people who – driven both by the world economy and their own desperate need to survive – are currently in the process of destroying the very place that provides them with this much-needed income.

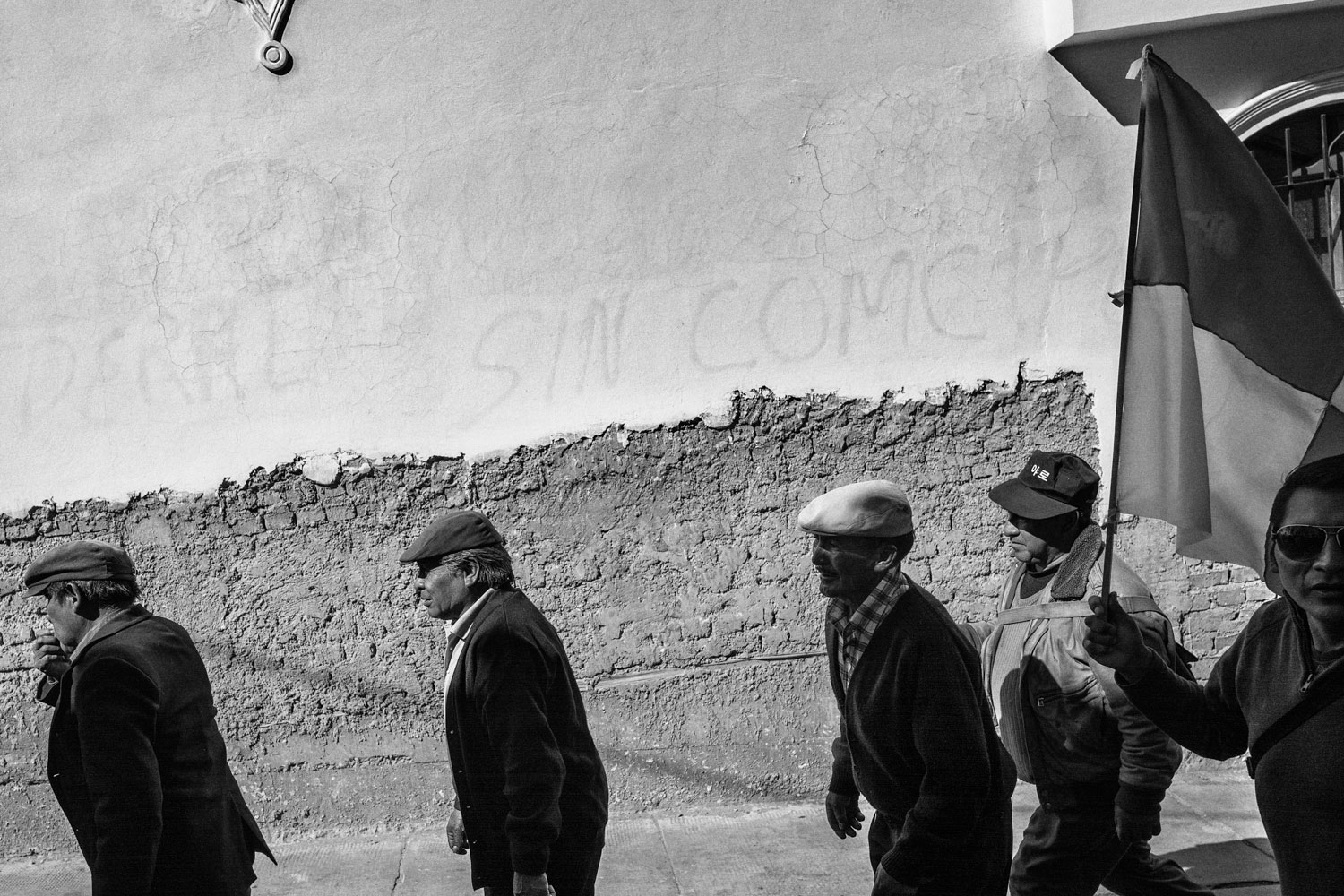

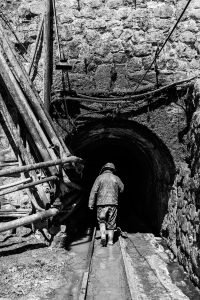

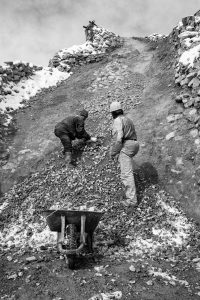

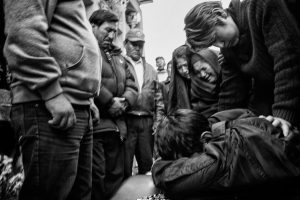

The Cerro Rico – the ‘rich mountain’ with an altitude of 4800 meters – is situated above the city of Potosí, historically founded by Spanish conquerors. Centuries of over-exploitation have left the mountain so riddled with tunnels that it would come as no surprise if it were to collapse in on itself at any day. So why are the mining plants, which in themselves are already run with shockingly low safety standards, not simply closed down? The answer is that mineral resources are among the few commodities Bolivia has in abundance – and that for the inhabitants of the barren mountain region, this is the only available source of work. From time to time protesting miners from Potosi clash with police in the capital, La Paz. They are calling on the government to make good on promises for public works and job creation in the southern Andean region.

In fact, Potosí is even expanding, as this is where people come when they give up on cultivating the barren highland soil. As a small cog in the global mineral-trade machine you can at least rely on a meagre income. Coca leaves and 90-percent alcohol make the daily grind more bearable. In the 16th century, the Cerro Ricco yielded the raw materials for the coins of the Spanish conquistadors. They subsequently flooded Europe with the currency to such an extent that it brought about the first inflation of world-historical proportions. Today it is predominantly tin and zinc that are mined from the mountain, largely for the global electronics industry. For anyone who has ever wondered what the supply chain that ends in our lifestyle accessories actually looks like, the area around the Cerro Ricco certainly paints a picture of where it begins.